Facial Recognition in the Ethical Crosshairs

(rimom/Shutterstock)

Facial recognition has become one of the most visible forms of AI, thanks to recent advances in deep learning and neural networks that have increased the accuracy to unprecedented levels. However, despite the progress, facial recognition technology has come under fire over concerns that it may be misused – by law enforcement, governments, and unscrupulous companies. Should it be banned?

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who is running for president on the Democratic Party ticket, has carved out a strong stance on facial recognition by declaring that he would push for a ban on use of the technology by law enforcement if he is elected president. Other presidential hopefuls have also expressed concern about facial recognition, but none have gone as far as Sanders in declaring that it should be banned.

The California legislature also took up the topic of facial recognition, and last week voted to pass a bill that would make it illegal to use the technology with video taken by police body cameras, but would still allow it to be used on fixed cameras. The bill is headed to the desk of Governor Gavin Newsom, who has until October 13 to sign it into law.

If signed into law, the Body Camera Accountability Act would make California the first state to ban the use of facial recognition technology. Massachusetts and Washington are also considering bans of their own, while some cities, including San Francisco and Oakland, have already banned its use within their jurisdictions.

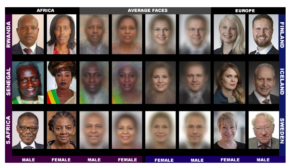

The debate over facial recognition spans multiple fronts. Backers of civil liberties cite issues of privacy, and the expectation that we will not be closely monitored as we move about a city. There are also issues of bias, specifically concerns that algorithms may have higher error rates detecting minorities, women, and individuals with darker skin tones.

Gender classification failure rates were significantly higher for darker-skinned women than lighter-skinned men, according to An MIT Media Lab researcher

For example, Joy Buolamwini, a graduate student in the MIT Media Lab, last year released the results of an experiment that called into question the accuracy of facial recognition products from vendors like Microsoft, IBM, and China’s Face Plus Plus. The study by Buolamwini, who is also a founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, concluded that the error rates for gender classification algorithms for darker-skinned women could exceed 34% while the maximum error rate for lighter-skinned males was less than 1%.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) conducted its own experiment that came to a similar conclusion. Using Amazon Web Services‘ Rekognition facial recognition software, the group built a model using 25,000 publicly available arrest photos. Then it used the model to find matches with photos of the members of the California State Legislature. According to the ACLU, the model “falsely matched 26 California legislators with random mugshots,” which would equate to a 22% error rate.

But this is where the details get a little hairy. When AWS caught wind of the experiment, it discovered that the ACLU had configured the model to signal a positive identification at a relatively low confidence level. “The 80% confidence threshold used by the ACLU is far too low to ensure the accurate identification of individuals,” stated Matt Wood, AWS’s general manager of product strategy. “We would expect to see false positives at this level of confidence.”

In London, the use of facial recognition technology in conjunction with police body cameras is igniting controversy (John Gomez/Shutterstock)

The large public cloud vendors are leading the effort to develop facial recognition software, as they do for many forms of AI that rely on the use of deep learning models to find patterns hidden across huge troves of data. That’s also the reason why political activist groups have demanded that AWS, Microsoft, and Google stop providing facial recognition technology to governments and law enforcement groups. So far, it doesn’t appear than any of them have made such a pledge. In fact, Brad Smith, Microsoft’s top lawyer, reportedly said it would be “cruel” to stop the government from using the technology.

Amid the pressure to ban the use of advanced facial recognition technology, some folks in the law enforcement community are pushing back against the efforts to ban facial recognition by positioning the technology as too valuable to give up. Ronald Lawrence, the police chief of Citrus Heights, California, and the president of the California Police Chiefs Association, says the potential benefits of using the technology to fight crime outweighs the privacy or bias concerns.

In an Op-Ed piece in the San Diego Union-Tribune earlier this month, Lawrence noted that the city of Detroit has experienced a 60% decline in car-jackings since 2015, when a citywide facial recognition network was implemented. He also credited facial recognition technology with assisting in the 2017 arrest of an MS-13 gang member who was wanted for murder in Northern Virginia. Other backers of facial recognition have noted how helpful the technology was in identifying the brothers behind the 2015 Boston Marathon bombing that killed three people and injured hundreds more.

“To put it simply: facial recognition software can be a valuable tool in identifying suspects of criminal activity,” Lawrence wrote in the Op-Ed. “It’s premature, and quite frankly reckless, for Sacramento politicians to prevent law enforcement from using this technology. Instead of banning facial recognition software, we should work together to address any areas of concern.”

Pranay Agrawal, the co-founder and CEO of AI services firm Fractal Analytics, has given this a lot of thought. Agrawal understands how useful AI technologies, such as facial recognition, can be for society. Fractal Analytics has deployed the same type of deep learning technology that’s behind facial recognition in hospitals, which have seen an increase in the accuracy rate of diagnoses for diseases like cancer.

“There are some fantastic and very useful and powerful applications of image recognition technology,” Agrawal tells Datanami. “It will be a change for the positive for the entire society. With that said, there are some serious issues with facial recognition by itself…The technology can spiral out of control very, very quickly.”

Civil liberties and protection of privacy would take a giant hit if facial recognition became widespread, Agrawal argued. If we go down that path, we wouldn’t be that far off from George Orwell’s Big Brother vision of a surveillance state, he says.

Civil rights and privacy advocates are aligning against use of facial recognition by governments and law enforcement agencies (MONOPOLY919/Shutterstock)

“Let’s say for a moment that you assumed that it was [controlled] by someone who is benign, someone who has great ethics and does all the right things,” Agrawal says. “Even then it would hamper my civil liberties and my existence.”

If you wanted to be part of a potentially controversial event, such an LGBTQ parade or a climate change parade, you may not participate if you knew the government was monitoring your activities, he says. “If I knew that my organization or the government could actually point out that Pranay Agrawal specifically participated in these five rallies, it would alter the way I behave,” he says. “I would choose not to go to those rallies now because I fear the repercussions.”

We are still in the early stages of deployment of advanced AI technologies like facial recognition, so it’s healthy to have this discussion. While it is used throughout the country, the technology is nowhere near ubiquitous, and there is no central authority using it to monitor the activities of citizens on a macro level.

If we want an example of what a nationwide facial recognition system might look like, we can look to China, where the communist government has amassed a database containing the images of every citizen in the country, a total of 1.4 billion people. Armed with a network of 200 million cameras, the government reportedly has the ability to correctly identify 90% of the population within several seconds.

“There are stories about how they’re using it to identity the Uighur, and they’ve now come up with the social score that’s impacting all aspects of life,” Agrawal says. “To me, those are all examples of how it should not be done.”

Related Items:

AI to Displace 40% of World’s Jobs, Predicts ‘Oracle of AI’

AI to Surpass Human Perception in 5 to 10 Years, Zuckerberg Says