Mathematica Helps Crack Zodiac Killer’s Code

The Zodiac's 340-character message resisted decryption for 51 years

Cryptographic researchers have finally cracked a 51-year-old code left by the Zodiac, a serial killer who terrorized Northern California in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Much of the work of cracking the code was done in Mathematica, the statistics package from Wolfram.

According to Discover Magazine, which wrote about the effort in a story published in its January/February 2022 issue, three researchers successfully cracked one of the messages attributed to the Zodiac killer, who authorities believe killed at least five people in the San Francisco Bay Area more than 50 years ago.

The researchers–including David Oranchak, a computer programmer in Roanoke, Virginia; Sam Blake, an applied mathematician at the University of Melbourne; and Jarl van Eycke, a Belgian codebreaker and warehouse worker–had all tried, unsuccessfully, to break the Zodiac’s 340-character code before joining forces in 2018, according to the Discover Magazine story.

Over the years, many have tried to solve the 340-character message received by the San Francisco Chronicle on October 14, 1969. This is believed to be the second cryptogram sent by the killer to the newspaper, the first being a 408-character message sent in August of that year that was decrypted just a week later (the killer subsequently sent two shorter messages, which so far have also resisted decryption).

But it wasn’t until the three started working in earnest during the downtime of the COVID-19 pandemic that they finally managed to decrypt it. The key breakthrough, according to the magazine, was Blake’s idea that the cipher is simultaneously a homophonic substitution cipher (in which plaintext letters map to more than one ciphertext symbol) and a transposition cipher (where plaintext characters are shifted according to a regular system).

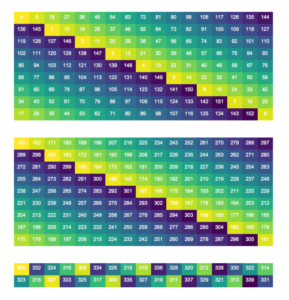

Visualization of the 1,2-decimation with the cipher split into three vertical segments, which finally yielded the meaning of Z340 (Courtesy Sam Blake)

With that theory in mind, Blake and Oranchak created thousands of possible solutions to the 340-character encrypted message (sometimes called Z340), using Wolfram‘s Mathematica stats package and a pair of encryption solutions, including AZdecrypt, which was created by van Eycke, and zkdecrypto.

They tried various direct transposition methods involving a direct offset of 18 or 19 characters. They looked for interesting patterns by transposing characters from the top-right corner, from the top-left corner, outside in, and inside out. Nothing. They tried one-step transpositions (moving down one row) two-step transpositions (down one row, then over two columns, etc.). Still nothing. They tried counting repeating bigrams, or pairs of symbols. Nothing. Finally, they tried combining all one- and two-step transpositions and repeating bigrams at the same time. Nope.

“Then we considered testing all 3-tuples of transpositions,” Blake wrote in a March 2021 blog entry on the Wolfram site. “However, this would require testing 155,929,364,660,224 candidate ciphers. Naively checking one a second would take over five million years. So we limited our experiments to decimations which would be reasonable to write out by hand and then only tested candidates with a high bigram count. Once again, this search turned up nothing.”

The researchers then decided that perhaps the key was breaking up the 340-character cipher. The 408-character cipher that had been cracked in a week had been delivered on three pages, so the researchers figured maybe Z340 was devised the same way. They split the cipher horizontally into two and three segments; vertically into two and three segments; and both horizontally and vertically into two and three segments. Then they used a “reduce” function to compute all possible segments, which resulted in proper two-dimensional decimations, Blake wrote. But it still didn’t yield the answer.

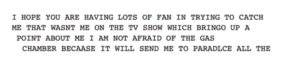

The plain text behind the Z340 cryptogram, as deciphered by the three researchers (Courtesy Sam Blake)

Finally, before beginning an exhaustive search that would utilize combinations of transpositions, the researchers went back and looked again at some of the 650,000 transpositions it had already tested. They found some interesting tidbits of plaintext, including the words “the gas chamber.”

“Investigating this result further, David used our 9,9,2-vertical segment, 1,2-decimation transposition and AZdecrypt to crib the phrases ‘HOPE YOU ARE,’ ‘TRYING TO CATCH ME,’ and ‘THE GAS CHAMBER,’” Blake wrote. “Eureka! After 51 years, we had decrypted some of the Z340.”

Eventually, the rest of the message came into focus (although not without using additional cryptographic techniques, including the good-old word scramble). Convinced they had solved the mystery, in December 2020 the researchers reached out to the FBI, which confirmed their work.

“Essentially all my work on the Z340 was done in Mathematica,” Blake wrote. “I used the Spartan high-performance computing cluster at the University of Melbourne to eliminate candidate transpositions using zkdecrypto and David used AZdecrypt. Otherwise, all the statistical analysis of the Z340 and the creation and analysis of the millions of candidate transpositions was done using Mathematica. The reason for my use of Mathematica is simple; it is by far the most time-efficient language I could use for such a task.”

A considerable amount of computational horsepower was required to find the solution to the Zodiac killer’s message, Oranchak told Discover Magazine. That would have made it almost impossible to have used this sort of brute-force approach to decrypt it back in 1969, he said. However, that doesn’t mean that today’s supercomputers can crack today’s encryption, since today’s encryption methods are much stronger.

“They’re just not amenable to this kind of attack,” Oranchak told the magazine. “The Zodiac cipher was almost certainly constructed by pencil and paper, but it was complex enough that it survived attacks for 51 years.”

While the Zodiac’s message has been decrypted, the identity of the killer remains an unsolved mystery.

Related Items:

Wolfram: Software the Hard Part

The Rise of Data Science Notebooks

Inside Cisco’s Machine Learning Model Factory